By Lisa Greim

To learn how to write, study the masters, we’re told. Note how the chapters in The Great Gatsby flow into one another. How does Flannery O’Connor deploy her objective correlatives? Notice how Tolstoy paces Anna Karenina, when he chooses to summarize, and when he slows down to let us experience all five senses in scene.

Another, not-so-well-known, way to learn craft is to read garbage.

Not-so-great American novels. Mediocre memoirs. Sad short stories.

Thinking about other people’s mistakes will sharpen your eye to see your own. It forces you to come to terms with the reality that your writing needs help, in a way that gives you the courage to keep at it, rather than resigning yourself to a lifetime behind a cash register at Lowe’s.

I guarantee you, every writer you admire has been down this road.

As a college junior, I had a revelation in a reading room of the old British Museum. It was not the beautiful domed chamber in which Karl Marx wrote Das Kapital, but a gray Thatcher-era warren of library stacks and study tables. Down the middle, a row of flat glass cases contained original manuscripts, the handwritten works of my literary heroes, from Jane Austen to John Lennon.

I spent the next hour making nose prints on the glass as I peered at the drafts up close.

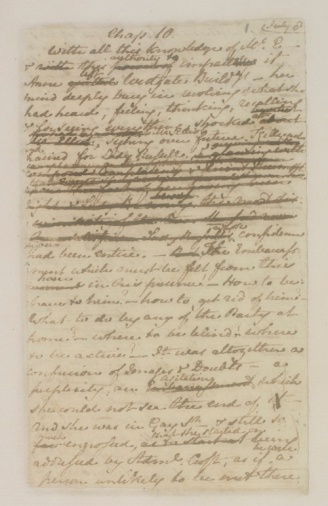

I mean, look at this page from Austen’s Persuasion. Do you mean to tell me that “good, quiet Aunt Jane” made this mess? Didn’t perfect prose fall out of her head and onto the page, women in Empire gowns gossiping behind their fans? Of course not. She struggled and second-guessed herself, like the rest of us.

Think that’s bad? Charles Dickens’ work was a disaster, full of bad handwriting and scratch-outs, embellished with either blots or beads of flop sweat. Dickens, perpetually in need of cash, published novels in installments to keep his audience happy and his creditors off his back. His pages show both his genius and his desperation, the work of a man with stories to tell and ten children to feed.

At the time I visited the British Museum, I was an English major, taking a short story workshop (with the great but terrifying F.D. Reeve, to whom I had been dispatched by my fiction mentor “to beat some discipline into you”) and a British novel class. Standing in the fluorescent light of that hallway, looking at the first drafts of authors I had either just read or was about to read, I realized for the first time that even for Woolf, Thackeray and the Brontes, writing was HARD.

If they could get from blots and scratchouts to Vanity Fair or A Room of One’s Own, maybe I could, too.

None of this is easy for anybody, I realized. In a self-published book of craft essays, This Won’t Take But a Minute, Honey, Steve Almond says that writers learn by workshopping other writers —our peers, not the authors of classics or prizewinners. “These folks have edited all their poor decisions out of existence,” he says. “That’s why they’re published.”

By identifying both merit and flaws in peers’ stories and figuring out ways to fix them, the writer strengthens his or her ability to make good decisions, what Almond (quoting Hemingway) calls your “Bullshit Detector.”

“If you look at a draft you wrote three months ago and all you can see is a mess of bad decisions, congratulations!” he writes. “You are making progress.”

Luckily for us, the universe has provided us many, many flawed works from which to choose.

Do yourself a favor and avoid bad bestsellers written by millionaires, which will just upset you. And don’t bottom-feed on Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing, which, for every self-published gem in its catalog, sells a hundred books by writers who didn’t feel

the need for either instruction or an editor. You’ll feel smug and superior for about five minutes. Beyond that, it’s like riding the Wild Chipmunk — a supposedly fun thing that gives you whiplash and a headache.

For your bad book study, I recommend second-rate titles from first-rate authors, people with talent who—you guessed it—made bad decisions.

Shelf-reading at the library in search of titles for my CW512 reading list, I picked up The Mistress’s Daughter, a memoir by the novelist A.M. Homes. In her novel May We Be Forgiven, she pulls no punches on the screwed-upness of the human condition: by page 14, as the narrator is in bed with his sister-in-law, his brother appears, sprung from a psych ward, and crushes his wife’s skull with a bedside lamp. This brother has already caused a fatal car wreck (page 4) and had a strip-naked-and-wet-yourself psychotic break (page 7). Talk about profluence! Holy cow.

So I looked forward to reading Homes’s own story, about meeting her birth mother for the first time at age 31. Her birth parents turn out to be as twisted as any characters she ever made up: her mother was 15 when she was seduced by her boss, a married man twice her age. He strung her along for seven years, set her up in an apartment, and when she got pregnant, dumped her.

Mom Ellen turns out to be scary and needy on the phone, and weird and stalkerish in person. The father’s no better; Norman answers the icebreaker question, “Tell me about yourself,” by announcing he’s not circumcised. Confronted with a bio-mom who demands Valentine’s gifts and whines, “You should adopt me and take good care of me,” and a bio-dad who meets her in low-budget hotels and criticizes her clothing, Homes’s fantasies of a happy family reunion vanish.

It is riveting stuff, but about halfway through, the energy leaks out. Ellen dies and Homes finagles a key to her house to collect some belongings, but sticks them in storage, unable to deal. She opens them years later, and confused at what she finds, searches Ancestry.com and public records, looking for answers. The book becomes a dry recitation of family history, and when the author tries to inject emotion by telling stories of her adoptive grandmother and her own daughter, they feel bolted-on. I skimmed through the last third, feeling cheated.

In the acknowledgments, a clue: the author thanks David Remnick. I tracked down her original piece, a New Yorker essay from 2004 that ended at exactly the point in the book that air started escaping from Homes’s narrative balloon.

A.M. Homes herself admitted to misgivings. “This reality thing is painful and overrated,” she told the Washington Post.

What I learned, as I struggle with the narrative arc of my own memoir, is to interweave or expand stories at your peril. A story has an organic beginning and ending, and if you need to pad it out by a hundred pages in order to make a book, you’re going to run into trouble.

Good stories are the grail, the star to steer by. Bad stories remind writers what it feels like to be a reader who sours on a text. They’re a vehicle for empathy.

When I sit down with a book, I try to read for both craft and story — falling into the tale as any regular human does, while keeping my writer persona perched on my shoulder. Hey wait, I might think. When did they tell me the heroine is an amputee? Did I miss something? Back I go in the text to find some mention of an accident or a prosthesis. I have a nasty habit of skimming, so this does happen.

When I don’t find the missing limb, I could just give up, throw the book against the wall and go watch America’s Got Talent. Instead, I try to analyze what the writer could have done instead. The next time I think it might be smart to pour a bunch of exposition into dialogue, or start a story in medias res just to keep the reader guessing, I can remember how I felt as a reader.

And then I pitch the book across the room, unless it’s a library book, in which case I place it gently on the passenger seat of my car for its trip home, although I may send it down the book drop with more than the required amount of enthusiasm.

Lisa Greim is a journalist and content marketing writer in Denver, and a student in the Wilkes University Graduate Creative Writing Program.

One thought on “Good Books Are Great, Bad Books Are Useful”